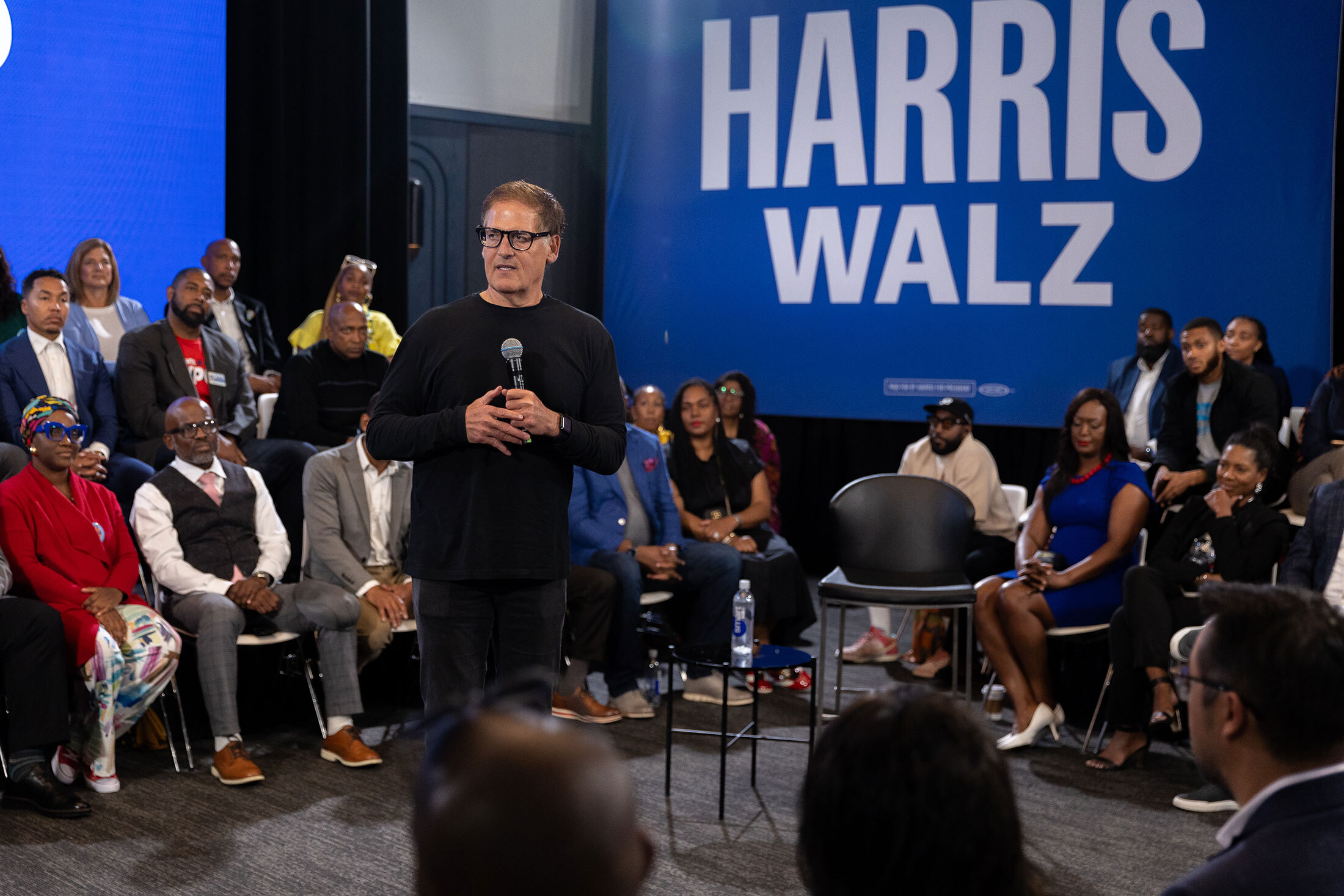

| Welcome to Bw Reads, our weekend newsletter featuring one great magazine story from Bloomberg Businessweek. Mark Cuban is a sports mogul, a small-business influencer, a media personality, a health-care disruptor and possibly the ultimate Donald Trump foil. Max Chafkin and John Tozzi write about the billionaire's work to lower health-care costs as well as his interest in politics. You can find the whole story online here. You can also listen to it here. If you like what you see, tell your friends! Sign up here. If Democrats were to try to design, from scratch, the most electable candidate for president in 2028, they'd probably start with an outsider. That could mean an elected official who's energetically committed to presenting themselves that way—either by way of a populist political program (New York Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez), or a willingness to show up on podcasts with right-wing provocateurs (California Governor Gavin Newsom), or a folksy Upper Midwestern affect (Minnesota Governor Tim Walz). But after nominating an octogenarian amid concerns about his competence, then switching candidates because of those concerns, and then losing anyway to a convicted felon who's already been impeached twice, Democrats may well conclude that the most electable candidate isn't a politician at all. That could mean an entertainer, a professional athlete or a celebrity rich guy—though the last option is particularly attractive since famous executives tend to have at least some actual executive experience. Of course, you'll need a very specific celebrity rich guy—prolific on social media and at ease in front of cameras, attributes that sound common but are actually quite elusive. Hypersuccessful businesspeople, surrounded by assistants and accustomed to speaking to audiences consisting of people they pay, can come off as aloof or robotic or hostile when confronted with the concerns of actual voters. It's hard to cultivate an everyman vibe from the cabin of your private jet. There are exceptions, of course. The most famous is Donald Trump: real estate developer turned name-rights-licensing mogul turned star of a Mark Burnett-produced reality TV show turned 45th and 47th president. The second most famous is Mark Cuban. Like Trump, Cuban is a billionaire with decades of experience playing a rich guy in the press. Trump did so first at 1980s hotel openings; for Cuban it was on the sidelines of games played by the Dallas Mavericks, the basketball team he bought in 2000 and then transformed into a perennial playoff contender. Like Trump, Cuban eventually took his shtick to network TV, starring, like Trump, in a prime-time reality show that was, like Trump's show The Apprentice, produced by Burnett. Cuban also has some time on his hands: He sold his controlling stake in the Mavericks in 2023 and recently recorded his final episode of Shark Tank.  The Benefactor executive producers with Cuban. Photographer: Frederick M. Brown/Getty Images The comparisons could go on: They're both avowed fans of Ayn Rand's The Fountainhead. They're both fixtures on the manoverse podcast circuit. They both like crypto. They've both been mocked for being less accomplished than their net worths would suggest. Not that Cuban wants to hear too much about these similarities. He and Trump have been publicly feuding for more than 20 years. "Get out," he says, nodding toward the exit after a Bloomberg Businessweek reporter gently suggests during an interview in April that the two men have had similar career trajectories. "That's the worst thing anybody's ever said about me." It isn't immediately clear whether Cuban intends to end the interview right there, but after glaring for a few seconds, he breaks into a grin. Even at age 66, the 6-foot-2-inch former college rugby player is physically imposing, but with a certain regular-guy ease. In his speech patterns and word choice, he still sounds like the working-class Jewish kid from Pittsburgh who hustled his way through high school and college, who tended bar and worked in a computer store in the 1980s. Cuban's first business was a modest tech consulting company he sold for $6 million. Then he got involved with a small streaming media company so he could listen to radio broadcasts of Indiana University basketball games on the internet. Cuban took over the company, renamed it Broadcast.com and sold it to Yahoo at the height of the dot-com bubble for almost $6 billion. "The difference," Cuban says, referring to Trump, "is he never had to start from broke." This is how Cuban sees himself—as a broke guy who worked his way into being a rich one. "If you can sell something door to door, your confidence goes through the roof," he said on Trevor Noah's podcast last year, rattling off a list of things he sold as a kid: baseball cards, garbage bags, magazines. He seems to relate to the always-be-selling part of Trump's character. In fact, as much as he can't stand the president, he grants that, in another world, he and Trump could easily be buddies. "I understand him," Cuban says. "If he weren't president, I wouldn't be involved in politics at all." Cuban's involvement in politics, to date at least, has mostly been a tease. He flirted with running for president in 2016 and 2020, but ultimately endorsed Hillary Clinton and Joe Biden. He supported Biden again in 2024, but very much half-heartedly. "If they were having his last wake, and it was him versus Trump, and he was being given his last rites, I would still vote for Joe Biden," Cuban told Bloomberg News when he visited the White House last year. Like much of what comes out of Cuban's mouth (and Trump's), the comment was a bit loopy—but it was apt and memorable.  Cuban answers questions at a town hall in Atlanta as part of the Harris-Walz campaign. Photographer: Nathan Posner/Anadolu/Getty Images Cuban, who identifies as an independent, became more involved in the race after Biden dropped out, frequently appearing on cable news as a campaign surrogate for Kamala Harris and even showing up with her at campaign events. At a rally in Wisconsin in October, he referred to Harris' opponent as "the Trump that stole Christmas" and "the Grinch" because, as Cuban argued, Trump's proposed tariff policies would make toys and other consumer goods expensive, ruining the holidays. Cuban's taunt looks prescient, even if it was mostly ignored at the time. He's annoyed about that, though his main complaint about Harris is more fundamental. "She didn't know how to sell," he says. "You have to be relaxed. You have to be open." Another way of saying this: Harris didn't act enough like Mark Cuban. Since the election, Cuban has been ubiquitous, talking to political journalists, showing up on pretty much every podcast, posting up a storm. His general pose has been to criticize Trump and Elon Musk while often not-so-subtly suggesting that he'd do a better job than either of them. Ostensibly he's doing this in service of his next act, a health-care venture known, immodestly, as the Mark Cuban Cost Plus Drug Co. The company offers generic medications, often for a fraction of what people pay through their prescription drug plans. It's the cornerstone of Cuban's plan to upend health care by throttling costs and reducing the vast inequalities in the system, all while working outside it. "The big picture vision is one, look for inefficient markets" in health care, he says. "And two, f--- it up." Cuban isn't the first billionaire trying to fix health care in the US. Around the same time he got involved with Cost Plus, Jeff Bezos, Warren Buffett and Jamie Dimon teamed up to launch Haven—a joint venture formed by their respective companies—that was supposed to lower health-care costs and simplify benefits. It went nowhere and folded in 2021. But there are reasons to take what Cuban is doing seriously. Cost Plus sells 2,500 drugs on its website—from asthma inhalers to pills for advanced prostate cancer—using a simple pricing equation. The company takes a 15% markup on what it pays to acquire the drug, plus $5 for dispensing and another $5 for shipping. A 90-count bottle of imatinib, a generic leukemia drug, was recently selling for $34.55 on Cuban's site. The same amount of the same medication at CVS Caremark—one of the three big pharmacy benefit managers, or PBMs—would cost $3,162.19, including $948.66 the patient would have to pay out of pocket, according to an estimate recently quoted to a Bloomberg reporter on the drug plan's website. Cost Plus doesn't accept the largest prescription insurance plans, such as Caremark, but for drugs like this it offers big savings even for people paying cash. The PBM industry argues that, examples like this aside, their plans tend to save money for people overall. And yet, that somebody with health insurance would be expected to pay 27 times the price Cuban charges for a generic medication is a source of embarrassment for the insurance industry and proof, in case anyone needed it, of the capacity of the US health-care system to bleed money from those it's supposed to be helping. Cuban's advocacy on drug costs has put him in a politically advantageous position—railing against a wildly unpopular industry while offering a solution that seems both sensible and nonpartisan. That, plus his history in politics, has led to speculation he might be preparing to run for president. "Cuban is almost wistfully seen as a guy who understands how to talk to voters," says Matt Angle, a longtime Texas political operative and founder of the left-leaning Lone Star Project. Cuban insists this isn't the case. "I don't see it," he says, citing a desire to continue working on Cost Plus and spend time with his family, though his actions suggest he might change his mind. "He's building a political profile to see if there's an appetite," says a Republican-aligned consultant who's been following Cuban's political activities since Trump entered the political arena and who asked not to be named because they were speaking without approval from their employer. "He's bored, he's ambitious, and it feels like he's been looking at this for 10 years." All of this makes Cuban unusual, especially in 2025. He is simultaneously the rare health-care reformer who's managed to find a way to put pressure on the industry, and the rare billionaire willing to pick a fight with Trump. Since November, pretty much every chief executive in America has tried to stay out of the line of fire, either by lying low or by throwing their support behind the president. This has created an opportunity for Cuban to take the opposite approach. Asked by anti-Trump activist Rick Wilson what caused him to become so vocal, Cuban smiled. "I got rich as f---," he said. "So I didn't have to care what anybody thought." In April a poll of self-identified Democrats and Democratic-leaning voters conducted by Yale University found that Cuban was seen as the most electable among all the major potential candidates, including all the Democratic front-runners. If it sounds absurd to suggest that the Shark Tank guy might be a contender to claim the Democratic nomination, consider the following: Donald Trump was elected president. Twice. Keep reading: Is Mark Cuban the Loudmouth Billionaire That Democrats Need for 2028? |